Bad Precedent

“No.”

Response of Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome H. Powell to question: “If the President asked you to resign, would you do it?” Interview by Neil Irwin (time mark 16:27), The New York Times, January 4, 2019.

Recent reports that President Trump wanted to fire Board Chairman Powell in response to Federal Reserve interest rate hikes are unprecedented. Denials from senior officials―Treasury Secretary Mnuchin and Council of Economic Advisers Chairman Hassett―have even less credibility than would a statement (or tweet) from the President himself. We find this entire discussion extremely disheartening and surely damaging to economic policy and the credibility of the Federal Reserve. As former Chair Yellen has stated, the risk is that people lose “confidence in the Fed, in the basis for its actions and its responsiveness to its mandate” (see here, time mark: 18:51).

To start, there is some debate over whether the President can fire the Fed Chair, other than “for cause.” We are not lawyers, but thoughtful people such as Peter Conti-Brown suggest that the answer is yes. The Federal Reserve Act (Section 10) specifically allows for removal of a Governor: “each member [of the Board] shall hold office for a term of fourteen years from the expiration of the term of his predecessor, unless sooner removed for cause by the President” (our emphasis). Based on precedent in other administrative settings, “cause” means that removal of a Governor from the Board would require a finding of inefficiency, neglect of duty, or malfeasance in office.

The Federal Reserve Act is silent about removing the Chair. The presumption appears to be that—even in the absence of “cause”—the President could dismiss the Chair from that role. However, that would not remove the Chair from his or her role as a Board Governor. In other words, even if ousted, Chairman Powell could choose to remain on the Board of Governors for some time to come (his term ends in 2028). We agree with former New York Fed President William Dudley who recommended that, should President Trump fire Chairman Powell, he should stay on as Governor.

Before moving to a discussion of the price we are paying for the President’s uniquely unorthodox behavior, it is worth explaining something about the governance arrangements at the Fed. Importantly, the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC), not the Board of Governors, makes monetary policy in the United States. The members of the FOMC include both the Governors (up to seven, but currently five) and the Presidents of the 12 Reserve Banks. While the Governors are always voting members of the committee, only five of the Reserve Bank Presidents vote in any given year. The rotation is complex, with the New York Fed President always voting, and the others voting every two or three years.

While the Federal Reserve Act specifies the membership of the FOMC, beyond giving the Chairman of the Board authority to call meetings and requiring that there be at least four meeting per year, it is silent on the details. In practice, this means that the Committee sets its own rules. In particular, the Committee elects its own chair and vice chair (the latter is traditionally the New York Fed President).

Two points are important here. First, U.S. monetary policy―and specifically interest rate policy―is set by a committee, not by an individual. While the Chairman of the Federal Reserve may be the public face of the FOMC, he or she is far from being a sole decision maker. While a chair always has a myriad of ways to influence committee’s decisions, other members can and do dissent. They also can sway others with compelling arguments. Second, while there is a tradition that the Chair of the Board is Chair of the FOMC, they are different jobs. There is no legal requirement that the same person fill both. This means that, while the President may be able to replace the Board Chair, selecting the Chair of the FOMC is up to the members of the committee.

If President Trump does succeed in firing Chairman Powell, we would urge his FOMC colleagues to keep him as their Chair. The point is that the FOMC will continue to follow its legal mandate in a nonpartisan way, and that its operational decisions—to raise, lower or maintain the current level of interest rates—are not subject to review by elected officials. Consistent with this goal, we hope further that, as the Committee’s Chair, Powell would continue to take on the responsibilities for FOMC communication―answering questions at the quarterly press conference, giving speeches without the disclaimer other Fed officials always include at the beginning of all their public remarks, and offering to testify to Congress in conjunction with the publication of the Fed’s semiannual Monetary Policy Report to Congress.

Returning to broader implications, President Trump’s attack on Fed policy and on the Chairman risks undermining decades of work to build a credible monetary policy framework with the transparency and accountability needed in a democratic society. After more than 100 years of the Federal Reserve, we have reached a much better understanding of the appropriate role of the central bank in American society. It is surely worthwhile to debate the appropriate scope and scale of the Fed’s operations, but there is no denying two things. First, inflation has now been low and stable for decades. Second, as painful as it was, the financial crisis of 2007-09 would almost surely have been far worse without the Fed’s aggressive stabilization efforts. Unemployment peaked at 10 percent, less than half the level in 1933; and output fell 4 percent from its 2007 peak, a fraction of the nearly 30 percent decline in the Great Depression.

The foundation of the Fed’s success since the early 1980s is a combination of independence and transparency that make the Fed’s policy commitments credible. Vast experience over decades (if not centuries) teaches us that independent, technocratic, central banks serve society much better than those run by politicians. They deliver lower and more stable inflation, and higher and more stable employment. As we have discussed on a number of occasions, central bank independence is a mechanism for overcoming the time consistency problem: the concern that policymakers will renege in the future on a policy promise made today. As we see now, there are times when monetary policy can be very unpopular. But, an independent central bank improves economic performance: it can achieve lower and more stable inflation rate without sacrificing long-run economic growth. Indeed, by anchoring long-run inflation expectations, it gains flexibility to respond to short-term shocks. (See our primers on central bank independence and time consistency.)

Furthermore, there are strong reasons to believe that transparency improves economic outcomes as well. Beyond the simple fact that it creates accountability, when a central bank communicates clearly, its policy will be more effective. First, it reduces the amount of uncertainty policymakers themselves create. Second, by elaborating a framework for policy, it allows investors to anticipate operational decisions, speeding the adjustment of financial conditions that influence the economy. And third, it makes conditional commitments possible, allowing policymakers to credibly address tail risks and keep them from materializing. (Dincer and Eichengreen provide evidence of the benefits of central bank transparency and independence.)

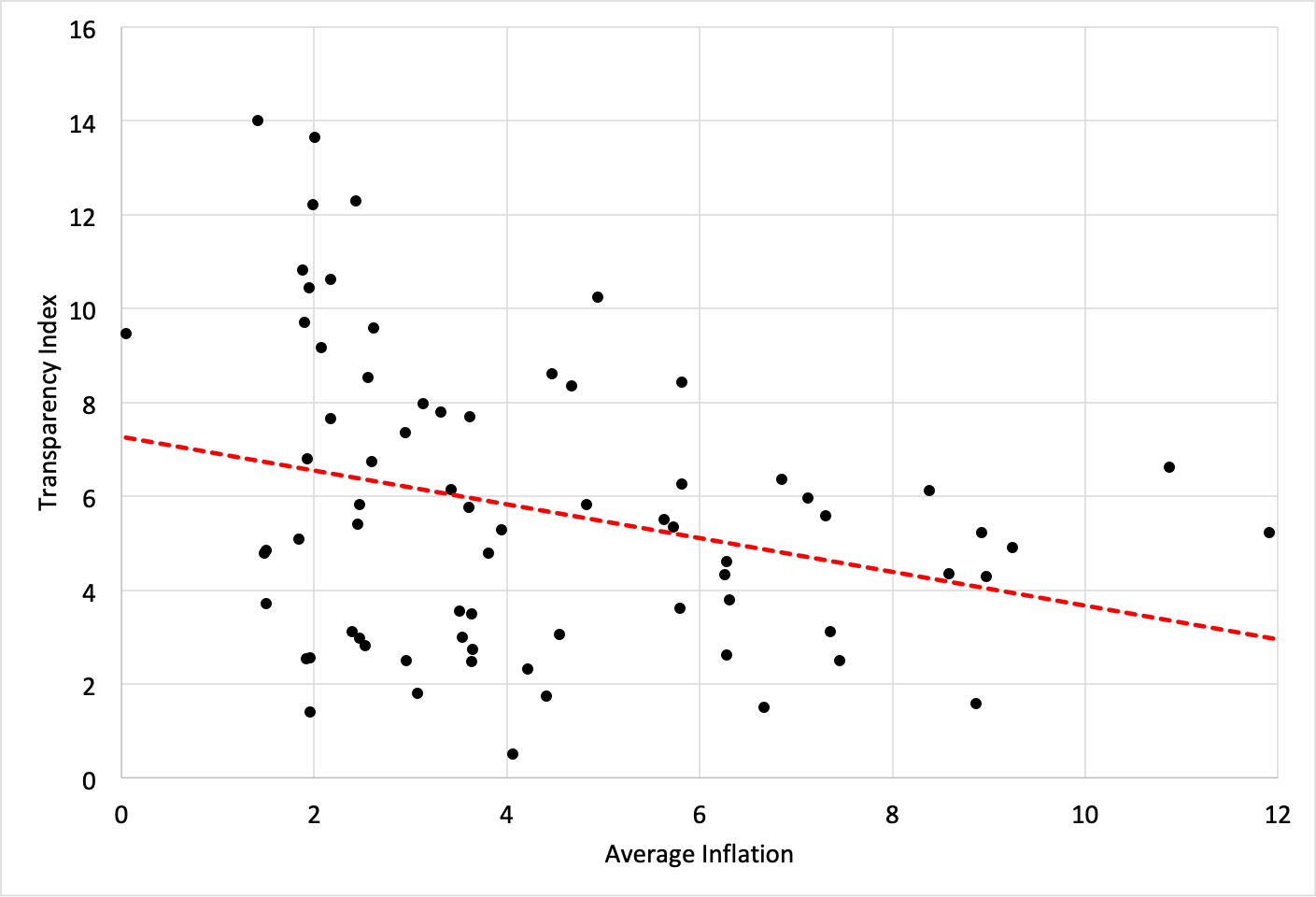

The result is that greater central bank transparency yields lower inflation (see the chart below). And, because lower inflation is correlated with less volatile inflation, greater transparency also is associated with lower uncertainty and undiversifiable risk. As Dincer and Eichengreen show, in a sample of more than 100 central banks, transparency has increased markedly since 1998. It comes as no surprise, then, that inflation is now lower and more stable not just in advanced economies, but in most emerging economies as well.

Relationship of Inflation to Central Bank Transparency

Source: Data are country averages from 1998 to 2014. Inflation is end-of-period annual data from the October 2018 IMF WEO database. The transparency index is from the Dincer and Eichengreen 2015 update.

Against this background, we view President Trump’s actions (and reported wishes) as the most serious attack on Fed independence since the Treasury-Fed accord of March 1951. Other recent threats, which came in the aftermath of the 2007-09 financial crisis, appear modest by comparison. In the wake of aggressive actions during and after the crisis to stabilize the financial system and restore economic growth, criticism of the Fed was at a fever pitch. In fact, an early draft of the 2010 Dodd-Frank Act went so far as to remove from the central bank all of its functions except for the formulation of monetary policy (see the discussion here). Even more recently, there were proposals to require the FOMC to account for its monetary policy actions with reference to a specific policy rule, as well as to subject various Federal Reserve activities to the Congressional appropriations process (see our earlier post here and here). None of these legislative plans was realized. And, in retrospect, none were as serious as the current episode.

For now, financial markets seem to be shrugging off President Trump’s pique as if it is empty talk. Like many market professionals and scholars, we admire Chairman Powell’s unswerving focus on carrying out the Fed’s mandate in a disciplined, professional manner. But it is impossible to put the genie back in the bottle. Fears that the President might fire the Chair likely will persist. And concerns that the President will use the two empty seats on the Board to appoint loyalists—rather than independent, technically skilled, policy setters—will linger. (Last week’s decision by Nellie Liang to withdraw from consideration for one of those seats further heightens that risk.)

Ideally, Congress would now repair the Federal Reserve Act to prevent the policy-driven firing of a Fed Chairman. Yet, expecting such congressional action would be a triumph of hope over experience. If, instead, the President makes good on the reported threat to fire Chairman Powell, the consequences would be tragic for the Fed and the country, with the after-effects lingering for a very long time.