Fiscal Dominance: A Primer

“[I]magine that fiscal policy dominates monetary policy. […] If the fiscal authority's deficits cannot be financed solely by new bond sales, then the monetary authority is forced to create money and tolerate additional inflation.” Thomas J. Sargent and Neil Wallace, “Some Unpleasant Monetarist Arithmetic,” Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis Quarterly Review, Fall 1981.

"Our Fed Rate is AT LEAST 3 Points too high. “Too Late” is costing the U.S. 360 Billion Dollars a Point, PER YEAR, in refinancing costs. No Inflation, COMPANIES POURING INTO AMERICA. “The hottest Country in the World!” LOWER THE RATE!!!,” Reuters citing President Donald J. Trump, TruthSocial post, July 9, 2025.

In recent decades, advanced economy central banks have set monetary policy independently of fiscal authorities. Their goals were a combination of price stability and maximum sustainable employment. Today, most announce inflation targets, adjust interest rates to keep inflation low and stable, and maintain accountability by answering questions in public.

Yet, economists have long known that fiscal developments can undermine the central bank’s ability to maintain price stability. In this post, we discuss the problem of “fiscal dominance” – when fiscal policy pressures or compels a central bank to forsake its price stability objective in favor of helping to finance the public debt. While heightened levels of public debt in many advanced economies suggest that the risk of increasing fiscal dominance – and of the loss of price stability – is widespread, our focus is on U.S. developments where the threat of fiscal dominance now appears to be acute.

Monetary Dominance, Fiscal Dominance and the World Between

The relationship between fiscal and monetary policy varies markedly both across jurisdictions and over time. At one extreme, public debt is on a sustainable path, so the central bank sets monetary policy without concern for the stance of fiscal policy. Such “monetary dominance” is necessary for keeping prices stable, but it is not sufficient. For example, despite a lack of extreme fiscal pressures, the Federal Reserve tolerated inflation that reached double-digit levels in the 1970s and early 1980s.

At the opposite extreme, when a government is unable to sell debt to the public, the central bank may be compelled to finance fiscal expenditure directly, regardless of the level of inflation. In that case, the policymakers have no choice but to issue non-interest-bearing money to finance the government. The resulting profit – known as seignorage – substitutes for the funds that the government cannot obtain by borrowing in public markets. And this monetary expansion fuels inflation.

In a world of extreme fiscal dominance, even a central bank that seeks to maintain price stability will fail. As Sargent and Wallace famously demonstrated, under common assumptions, the expectation of future money creation – compelled by the need to finance prospective government spending – leads to higher inflation today (see the opening citation). Such episodes are often associated with wars and civil strife that lead to hyperinflation.

Between the two poles of pure monetary and pure fiscal dominance lies a broad range of circumstances in which a government may seek to pressure a central bank to lower the cost of debt. Unsurprisingly, the larger the debt service and the larger the prospective fiscal deficit, the greater the incentive for fiscal policymakers (i.e. politicians) to exert such pressure on the central bank.

In these “intermediate” cases, the central bank faces a tradeoff between satisfying fiscal needs and keeping prices stable. For example, to ease their financing burden, fiscal policymakers may pressure the central bank to lower the policy rate below the level consistent with its inflation target. Fiscal policymakers would benefit in the short run both from the lower cost of new debt issuance and from a surprise inflation that lowers the real value of outstanding debt – analogous to a partial default. Eventually, however, lower interest rates drive inflation expectations, and then inflation, markedly higher, leading to a loss of central bank credibility.

Fiscal Dominance in History: Extreme and In-Between

The history of hyperinflations shows that fiscal dominance, even in its extreme form, is disturbingly common. In a hyperinflation, the sole purpose of the central bank is to finance the government. Yet, a hyperinflation eventually wipes out the benefit that the government receives from central bank money creation. Experience shows that hyperinflations end only with the restoration of fiscal stability, often accompanied by the introduction of a new currency to replace the worthless, discredited old one.

Hanke and Krus identify 58 episodes of hyperinflation, defined as periods when prices rose continuously by more than 50 percent per month. With the sole exception of France’s revolutionary hyperinflation at the end of the 18th century, the Hanke-Krus list begins in 1920. Importantly, each World War created widespread economic and financial distress which then led to a wave of hyperinflations. The case of Hungary in 1946 – where prices doubled every 15 hours – was the most severe. To meet the government’s payment obligations, Hungary’s central bank eventually issued the highest denomination currency note on record – a one followed by 20 zeros (see image below). By comparison, Germany’s infamous post-World War I hyperinflation of 1921-23 was only the fifth most acute, with prices doubling every 3.7 days. Nicaragua’s hyperinflation, which ended in 1991, is the longest at 58 months; while Venezuela’s, ending in 2022, is the most recent.

Hungary (1946): Central Bank Note with Face Value of 100 quintillion (1020) pengö

Source: Author’s image.

Bouts of high inflation – well shy of hyperinflation – usually reflect government pressure on the central bank to keep interest rates low to reduce the cost of selling debt to the public. In these episodes, the fiscal policymaker’s actions undermine the central bank’s independence and the credibility of its commitment to price stability. Put differently, there are cases between the two extremes of monetary and fiscal dominance in which inflation reaches double-digit levels because the central bank accommodates government wishes to lower the cost of public finance. While less destructive than a hyperinflation, we still view these as cases of fiscal dominance.

Consider two recent intermediate examples: Argentina and Türkiye. In both cases, political pressures on the central bank to keep interest rates low led to annual inflation of more than 50 percent from 2022-24. Restoring price stability requires reversing that pressure. In Argentina, inflation slowed after the new Milei government’s aggressive fiscal consolidation at the end of 2023. In Türkiye, it was tighter monetary policy over the past two years that helped bring inflation down. Yet, in both countries, inflation remains above 30 percent annually. One reason may be the lingering impact of political influence on perceptions of central bank credibility.

Keeping Prices Stable

Historically, episodes of stable prices require unambiguous monetary dominance and a modicum of fiscal restraint. In the past, commodity currencies helped discipline fiscal behavior (at least in the absence of war) because large fiscal deficits typically could only come with politically humiliating devaluations. When the Gold Standard ended in 1973, public debts in advanced economies were low. This allowed central banks to introduce inflation targeting and establish a lengthy record of price stability.

However, inflation targeting did not prevent the unsustainable buildup of public debt that now poses a risk. So far, leaving aside the pandemic, advanced economy central banks generally have managed to keep inflation low. Even in Japan where net government debt exceeds 130 percent of GDP, consumer price inflation averaged less than 0.4 percent per year over the past 25 years. Now, however, higher inflation and interest rates in Japan are boosting the cost of debt service, adding to the incentive for fiscal dominance: at 1.6 percent, Japan’s 10-year yield is nearly two percentage points above its 2019 low and at its highest level since 2008.

History and Prospects: Fiscal Dominance in the United States

Aside from Japan, the greatest risk of fiscal dominance among advanced economies today is in the United States, reflecting the rapid increase in the cost of financing the U.S. federal debt. Two factors contribute to this cost surge: (1) the buildup of the public debt itself, and; (2) the post-pandemic rise of the interest rate on that debt.

First, persistently large deficits are propelling debt held by the public markedly higher. As the following chart highlights, public debt (as a percent of GDP) jumped twice in the past 20 years – first because of the 2008-09 financial crisis and then again with the COVID pandemic. Going forward, the Congressional Budget Office anticipates a continued rising trend, with a new debt ratio record projected for 2028.

Federal Debt Held by the Public (Percent of GDP), 1940-2035P

Source: Congressional Budget Office, The Budget and Economic Outlook: 2025 to 2035, , Figure 6.

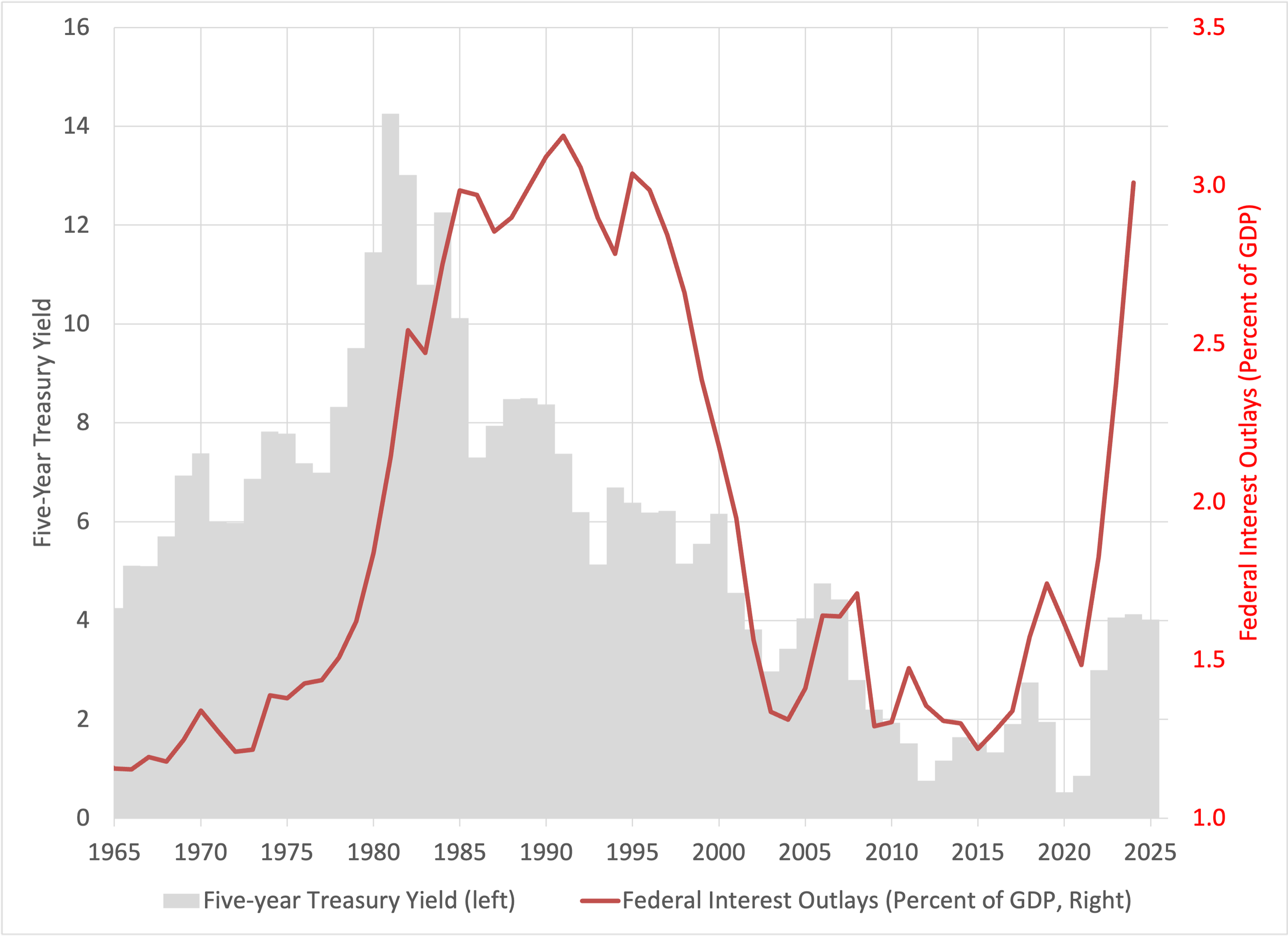

Second, as the federal debt rises, so do the payments needed to compensate the holders of Treasury debt. As a result, U.S. debt service as a percentage of GDP is now at a level rarely seen in the past 60 years (see the red line in the following chart).

United States: Federal Interest Outlays (Annual, Percent of GDP) and the Yield on Five-year Federal Debt (Quarterly), 1965-2Q 2025

Note: With the average maturity of federal debt at about six years, we use the five-year Treasury yield as a proxy for the average interest cost. Yet, due to a wave of short-term borrowing during the pandemic, about one-third of marketable federal debt matures in 2025 and again in 2026, adding to interest rate sensitivity (see here).

Source: FRED Yield (DGS5) and Interest Outlays (FYOIGDA188S).

To get a sense of the increased sensitivity of U.S. federal debt service to market interest rates, note that in the previous episodes of very high debt service – starting around 1985 and extending for more than a decade – the average yield on federal debt (proxied by the five-year Treasury yield shown in grey bars) was as much as double the current level. Today, with higher levels of public debt, a relatively low yield by historical standards is sufficient to generate high debt service costs. Put differently, a sustained one-percentage-point rise in the average yield now adds over one percent of GDP to the annual cost of federal finance: that is more than double what an equal yield increase added in the mid-1980s.

Perhaps the biggest risk of fiscal dominance today comes from the extreme threat to U.S. central bank independence. The Federal Reserve officially gained independence with the Banking Act of 1935 (see Richardson and Wilcox). Shortly thereafter, however, World War II introduced a period of fiscal dominance. To facilitate the massive government deficits needed to finance the war, the Fed purchased sufficient Treasury debt to ensure long-term interest rates (and hence government financing costs) remained low. Price controls suppressed inflation during the war but did not prevent a bout of double-digit inflation thereafter. It was only in 1951 that the Treasury-Fed Accord restored the central bank’s authority to set interest rates independently, ending this episode of fiscal dominance (see Hetzel and Leach).

Today, fiscal developments once again threaten Federal Reserve independence. One indicator of rising fiscal dominance is the political pressure to cut interest rates below the level most U.S. central bankers believe to be consistent with achieving their 2 percent inflation goal. Specifically, a majority of the Federal Open Market Committee expects policy rates – currently in the 4 to 4¼ percent range – to stay above 3 percent through 2028 (see Figure 2 in the September 2025 Summary of Economic Projections).

Yet, while declaring the economy to be strong, this summer President Trump called on the Fed to lower interest rates by at least three percentage points (see opening citation). His stated concern was the high cost of servicing the federal debt (“360 Billion Dollars a Point – PER YEAR”). Similarly, the President’s newest appointee to the Fed – his once-and-future CEA Chief Stephen Miran – also called for sharp interest rate cuts this year.

Since returning to office in January, President Trump’s attempts to pressure the Fed have broadened and intensified. He has repeatedly called on Chair Jerome Powell to resign and reportedly considered firing him (see here and here). In August, he moved to fire Governor Lisa Cook “for cause,” but she remains in office pending a Supreme Court ruling (see here). His September selection of Stephen Miran to take an open seat on the Board of Governors suggests a preference for more far-reaching changes at the Fed: prior to his appointment as CEA Chair, Dr. Miran proposed reforming the central bank to allow the President to remove Governors “at will”, rather than “for cause” (see page 11 here). Making the Fed Governors serve at the pleasure of the President would remove a key foundation of Federal Reserve independence, making the central bank far more amenable to short-term political pressures.

Looking at the current circumstance, President Trump could at any time name the successor of Chair Powell, whose term as Chair ends in May 2026 (and as Governor in January 2028). If Chair Powell steps down as Governor when his term as Chair concludes, President Trump will have the opportunity to appoint his fourth of seven Board governors. As we recently highlighted, the Board influences the appointments of Reserve Bank Presidents, allowing it eventually to determine the makeup of the Federal Open Market Committee that sets monetary policy.

Oddly, despite these transparent executive statements and actions that favor greater fiscal dominance, and despite the unsustainable path of U.S. fiscal policy, the marginal cost of financing U.S. debt has eased notably this year. At this writing, the 10-year yield is slightly below 4 percent, down by about 75 basis points since January; while the two-year yield (now 3.48 percent) is down over the same period by more than 90 basis points. Even market long-term inflation expectations declined slightly this year.

Yet, experience teaches us that actual fiscal dominance – in which the Federal Reserve prioritizes fiscal needs over price stability – would be inconsistent with these favorable Treasury market developments. Perhaps market participants doubt that the President will follow through on his efforts to pressure the Fed to lower its policy rate if inflation remains significantly above 2 percent. Yet, if he does follow through, and if the Fed proves unable or unwilling to resist, the resulting loss of central bank credibility could usher in a bout of much higher U.S. inflation than bond market participants currently expect. Put differently, aside from limited short-term benefits, fiscal dominance as a policy option is doomed to fail.