Are stablecoins really the future of payments?

Since January 2025, the U.S. Government has undertaken numerous measures to promote the use of crypto. The most prominent is enactment of the GENIUS Act, a regulatory framework for “payments stablecoins.” These are reserve-backed tokens with value pegged to a government-issued currency, predominantly the U.S. dollar.

Currently, the two largest stablecoins, Tether’s USDT and Circle’s USDC, have a combined market capitalization of more than $230 billion and operate on the Ethereum blockchain. Each originated as a stable-valued means of payment for people trading inside the crypto world. They quickly turned into the primary bridge between the traditional financial system and the crypto world, allowing investors and speculators to shift funds between established financial instruments (equity, bonds, bank balances, and the like) and crypto assets (Bitcoin, Ether, Solana, etc.). At this writing, this remains stablecoins’ primary use.

The original dream of crypto enthusiasts – a fully decentralized system operating without intermediaries or governments – has given way to a far less radical vision that requires government oversight and the legal enforcement of property rights. Indeed, stablecoin issuers (and some other promoters of crypto) are now strong advocates of government regulation.

In this post, we compare payment stablecoins against a likely competitor, tokenized deposits. The latter are programmable, unique, digital representations of a traditional bank deposit. The comparison leads us to anticipate that – outside of the crypto world – tokenized deposits will have compelling advantages. In any case, as crypto firms seek to enter traditional finance, large banks will have powerful incentives to innovate to sustain or expand their market share.

The GENIUS Act

As is the case with every industry, the people controlling crypto wish to have a say in the regulations, so they work to control the political process. Aside from populating the Trump Administration with digital asset advocates, the main result of this lobbying effort thus far is the GENIUS Act. The Act has three key provisions: First, it prohibits the issuers from paying interest (Sec 4. (11)). Second, it restricts the assets that an issuer must hold in the reserve backing the stablecoins (Sec 4. (a) (1) (A)). Third, issuers must meet the requirements of the Bank Secrecy Act, complying with Know Your Customer (KYC), anti-money laundering (AML) and anti-terrorist financing (ATF) standards (Sec 4. (5)). We now consider each of these.

Prohibition on interest payments. To be sure, history teaches us that there are many ways to evade restrictions (such as usury laws) on the payment of interest. Standard methods include charging higher prices to borrowers or offering other types of compensation to lenders: for example, Islamic banks may purchase a house or a car, selling it to the customer at a higher price with repayment in periodic installments. In the case of stablecoins, Coinbase and PayPal already offer significant “rewards” – currently 3 to 5 percent – to customers holding stablecoin balances (see also Bank Policy Institute).

Restrictions on reserve assets. The list of eligible reserve assets is short, and most items on the list (such as short-maturity Treasury instruments) are virtually free of risk. However, payment stablecoin reserves also may include prime money market funds (with variable net asset value) and bank deposits. A sufficient concentration of a stablecoin’s reserves in a prime money market fund that faces a run could trigger a run in the stablecoin itself.

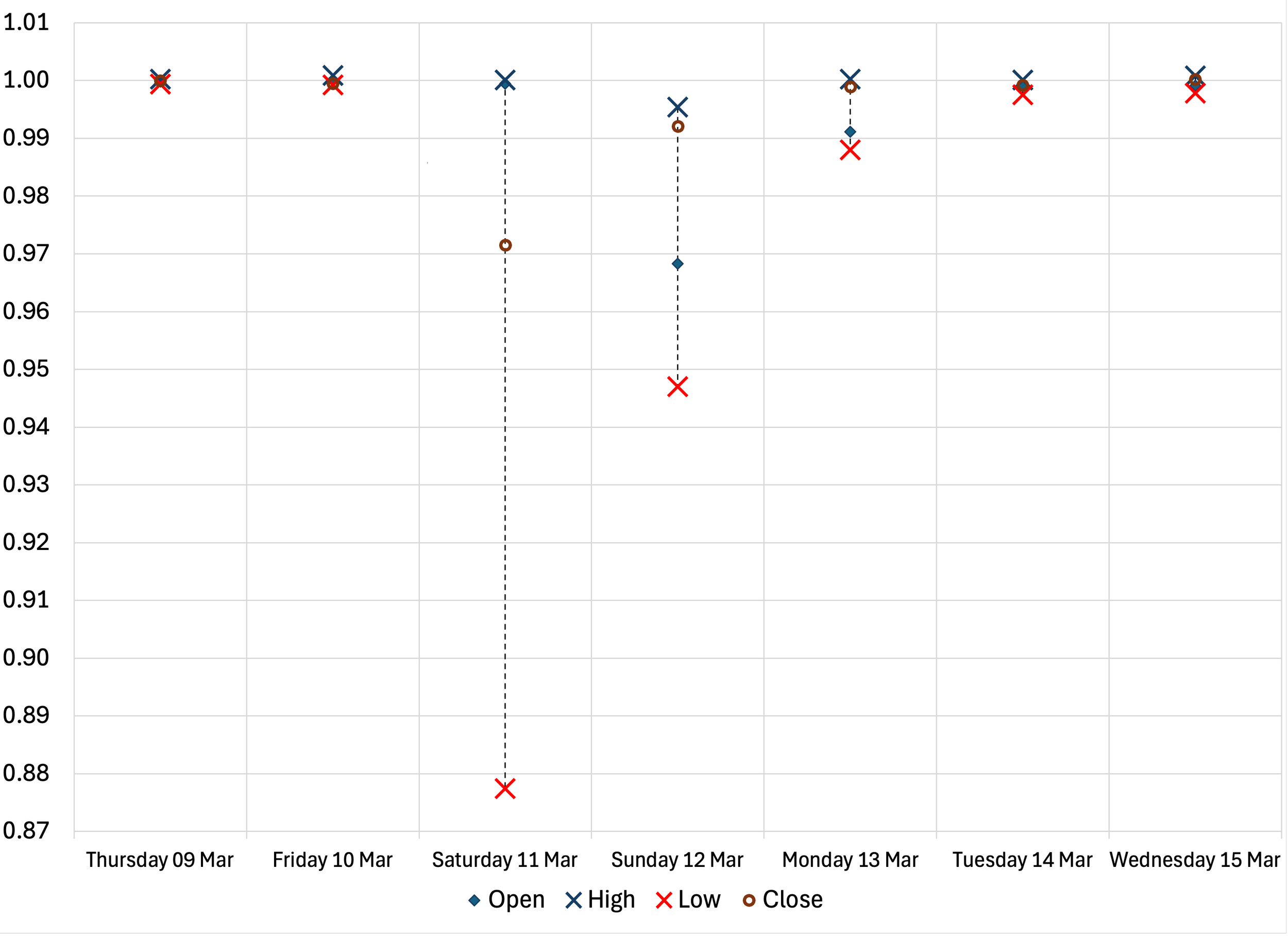

And uninsured bank deposits are a well-known source of runs on both banks and associated stablecoins (Acharya et al. and Jiang et al.). The 2023 collapse of Silicon Valley Bank and the subsequent run on USDC illustrates the fragility of stablecoin balance sheets that could persist even under GENIUS Act rules. Recall that Circle’s reserves for USDC included a $3-billion deposit at SVB. Following SVB’s failure on Friday, 10 March 2023, doubts emerged that uninsured depositors such as Circle would be able to recover their funds. The next day, USDC’s price plunged, falling as low as $0.8774, (see Figure 1). USDC returned close to parity only after U.S. policymakers undertook emergency actions on Sunday, 12 March, to protect all SVB’s depositors, including the uninsured ones such as Circle. Importantly, the run on USDC extended well beyond price instability: between 7 and 20 March 2023, USDC’s market capitalization fell from $43.6 billion to $35.3 billion, indicating that over a two-week period Circle sold 20 percent of USDC’s assets to meet redemptions.

Figure 1. Daily Trading Range of USDC, 9 March 2023 – 15 March 2023

Source: Coinmarketcap.com.

Despite these risks, the GENIUS Act does not oblige regulators to impose a capital requirement on the issuers of payment stablecoins. If regulators do opt to do so, capital requirements on these issuers may not exceed what is “sufficient to ensure the ongoing operations.” (Sec. 4. (4) (A) (ii)). Absent some capital to buffer potential losses, it is doubtful that stablecoins would become a safe, information-insensitive asset in the sense of Dang, Gorton, and Holmstrom.

Bank Secrecy Act requirements. When it comes to KYC, AML and ATF standards, matters are a bit more complicated. There are two common ways for an individual to hold crypto assets, including stablecoins. One is through a licensed or registered intermediary and the second is using a noncustodial or self-hosted wallet. In the first case, the custodian (such as Coinbase) will have a consolidated “account” holding all the stablecoins it has in custody at its address (or addresses) on the blockchain. As a registered intermediary, this custodian must ensure that its customers are not using stablecoins for an illicit purpose.

The alternative is that the holder uses a noncustodial wallet, maintaining full control of their crypto holdings. Since stablecoins are bearer instruments, ownership is not registered, and the holder can remain anonymous. In this case, there is no guarantee that the stablecoins will be used solely for legal activities. But under the GENIUS Act, stablecoin issuers must abide by the Bank Secrecy Act, both ensuring that their customers are not using their stablecoins for an illicit purpose and reporting their customers to enforcement authorities if the issuers detect suspicious actions. At this stage, it is unclear how the issuers will perform this important function.

A related question is whether it is possible to determine the physical location of the owner of a stablecoin. Authorities would like to ensure that the reserves backing stablecoins are held inside the same jurisdiction of the people who hold the stablecoins. This “co-location” would ensure that they can enforce redemption guarantees. Whether this is possible remains to be seen.

Stablecoins vs. Tokenized Deposits

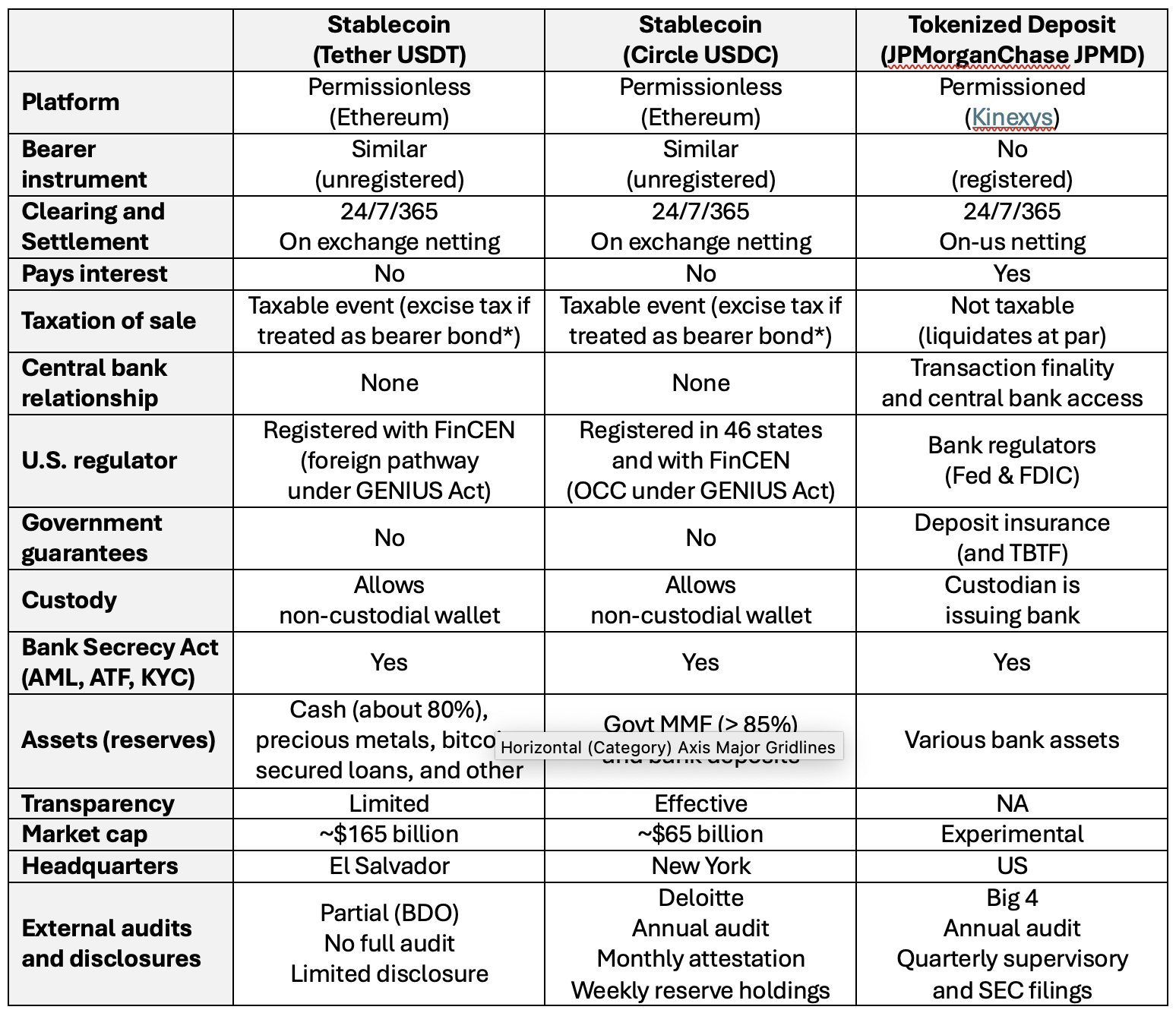

Ultimately, the key question is whether people will want to hold stablecoins for use as a payment instrument outside of the crypto world. To address this question, we compare the two largest stablecoins to a specific version of what we see as their most likely competitor: tokenized deposits. Figure 2 compares Tether’s USDT and Circle’s USDC with JPMorganChase’s JMPD. Of the 15 features that we consider, the three instruments share only two: they clear and settle around the clock (24/7/365) and are subject to the anti-crime provisions of the Bank Secrecy Act (KYC/AML/ATF).

Looking at the two stablecoins, they are the same across many dimensions. They are both recorded on the Ethereum blockchain, are unregistered bearer instruments, pay no interest (from the issuer), face the same tax treatment, have no relationship with the central bank, have no government guarantees, and allow for noncustodial wallets. USDT and USDC differ primarily in their transparency, the nature of their auditing, the composition and segregation of their reserve assets, and the location of their headquarters. In all these areas, USDC appears less risky. Most notably, it has faced a complete audit by a Big 4 accounting firm, it holds most of its reserves (currently 85 percent) in the Blackrock Circle Reserve Fund, and its location is in New York City, where it faces oversight by the State of New York Department of Financial Services. It is worth noting that the New York stablecoin rules regarding reserves, redemption and external attestation established a precedent for the GENIUS Act framework.

Figure 2. Key Features of Tokenized Programable Payment Vehicles

Source: Authors, except where stated.

* Excise tax under Tax Equity and Fiscal Responsibility Act of 1982 (TEFRA)

AML Anti-money laundering. ATF Anti-terrorist financing. KYC Know your customer.

The characteristics of stablecoins stand in sharp contrast to those of a tokenized deposit, in this case JPMorganChase’s JPMD, which aims at institutional clients and is in an experimental stage.

Importantly, JPMD largely has the same properties as an existing deposit, so it can rely on the established governance that exists for deposits both domestically and internationally. JPMD pays interest, liquidates at par, is insured by the FDIC, is issued by a too-big-to-fail bank with central bank access, and is backed by JPMorganChase’s entire balance sheet. In addition, it can be issued in various currencies, allowing for an internal market for cross-border and foreign exchange settlements. If our reading is correct, the design of JPMD would allow two institutional clients, one in Europe and one in the United States, to instantly settle a payment in dollars or euros (or even a payment that involves a currency conversion) on the balance sheet of JPMorganChase.

JPMD differs from existing deposit accounts in three important ways. First, it clears and settles around the clock. Second, the plan is that JPMD will allow for programmable settlement and automated functions through smart contracts. That is, it can implement conditional payments as well as streamline recurring payments, insurance claim payouts, government aid benefits, and the like. It is even possible to build eligibility directly into the instrument, effectively embedding compliance. Third, JPMD can trade either on a proprietary centralized ledger operated by JPMorganChase or, using smart programming to provide access only to approved clients, on a public, distributed ledger.

The Advantages of Tokenized Deposits

For an institutional client, JPMD would seem to offer compelling advantages over stablecoins. (Liang speculates that tokenized deposits and faster payments also may suffice for the needs of most consumers). First and foremost, the issuing entity (JPMorganChase) has a reputation for integrity that it has established globally over decades. It operates in multiple regulatory environments, serving customers in more than 100 countries. It has long experience both with cross-border transactions and with data protection in multiple jurisdictions. It can credibly ensure continuity of operation based on a deep and broad pool of high-quality employees and a robust physical infrastructure.

No less important, JPMorganChase operates under strict regulation and supervision. Its safe-haven status has allowed the bank to gain strength repeatedly amid (and in the aftermath of) financial crises. And, especially for institutional clients, there is additional comfort from the exclusion of illicit players from the firm’s proprietary platform: Users can rest assured that JPMorganChase will police hackers, sanctions evaders, terrorists, and other criminals. As a result, the latter will almost surely view public, distributed ledgers and pseudonymous coins without location markers as easier venues and tools to ply their trade. Put differently, there are strong reasons to believe that JPMorganChase’s proprietary ledger will be both more efficient and more secure than a permissionless blockchain where stablecoins reside (see Bakos and Halaburda).

To this already lengthy list of advantages, we add one big one: the ability of a behemoth bank to exploit network externalities. Recall that a network externality occurs when the value of a good or service rises with the breadth and intensity of use. Technology platforms are famous for such externalities. Examples include operating systems (Microsoft, Apple, and Linux), search (Google), and internet shopping (Amazon).

Outside of China, JPMorganChase is the largest global bank (with assets of roughly $4 trillion). When it offers customers a product, they are drawn into an ecosystem with tens of millions of existing customers and a wide array of complementary products and services. In this context, as the number of customers using JPMD increases, the internal (“on us”) market will grow more liquid, with the potential for instant settlement both within and across borders at minimal cost.

We should add that tokenized deposits could become even more competitive than the instruments issued by a single institution that we discuss. Imagine, for example, that a group of internationally active, systemic banks decide to accept each other’s tokenized deposits instantly at par. In effect, they would be implementing a digital version of the 19th century U.S. check clearinghouses that assured the expeditious settlement of most payments, imposed credit standards and even acted as private lenders of last resort (see Bernanke). Such a 21st century clearinghouse would be a too-big-too-fail juggernaut.

The Disadvantages of Stablecoins

To what extent can stablecoin issuers compete? Outside of specific crypto-related niches, who would prefer an instrument that lacks common global governance standards, pays no interest (at least from the issuer), has no insurance, is issued by an entity that lacks central bank access, has less experience in meeting compliance and data protection requirements in multiple jurisdictions, lacks an internal market of behemoth breadth and scale, and may have a history of illicit use and reputational problems? (For a discussion of illicit uses of crypto see Chainalysis; for an analysis of governance issues in the crypto ecosystem, see Berner, Coen and Wilkins).

Stablecoins also lack three essential features that the Bank of International Settlement associates with any effective payments instrument: “singleness”, “elasticity”, and “integrity”. We can summarize these shortcomings by highlighting: 1) the tendency for stablecoins to deviate from their par value of one dollar (a violation of singleness, see Figure 1); 2) the fact that nonbank stablecoin issuers lack access to the central bank (a violation of elasticity); and 3) illicit uses of crypto remain notable (a violation of integrity).

We conclude this section with a brief discussion of three problems with stablecoins that tokenized deposits do not have. First, because they are issued and controlled by banks, tokenized deposits can offer holders the privacy protection that meets the standards in their home location while still providing for the ability to monitor and transfer funds across jurisdictions. By contrast, since stablecoin ownership is recorded on a public blockchain, transactions are traceable by anyone with the appropriate tools.

Second, tokenized deposits need not create the same cross-border risks as stablecoins. As Portes notes, the fungibility of stablecoins means that redemption may not occur in the same place as issuance. To see the risk, consider a case where two issuers (possibly subsidiaries of the same parent) issue the same stablecoin in two jurisdictions (possibly with different reserve-backing requirements). Suppose that someone purchases this stablecoin in one jurisdiction and redeems it in the other. Fungibility means that no one (except possibly the holder) knows who originally issued the stablecoin. Will reserve assets automatically migrate to the place where stablecoin redemptions occur? If not, limited mobility of reserves could augment stablecoin run risks and transmit them across borders. (In the absence of ring fencing of bank balance sheets in different jurisdictions, we can think of tokenized deposits and their associated assets as if they are on the consolidated balance sheet of the issuing entity. As a result, the issuer can redeem tokens in cash in any jurisdiction where they operate.)

Third, unlike stablecoin issuers, whose products are mostly dollar-linked, the world’s largest banks already accept deposits in a number of currencies. And while payment stablecoins may remain predominantly dollar-based, going forward, banks likely will seek to create tokenized deposits in the currencies where they find opportunities to lend. Non-US regulators are likely to find such bank innovation far less troubling than an expansion of Treasury-backed stablecoins that may invite currency substitution.

Conclusion

To foster greater efficiency and access in the financial system, the U.S. Government has undertaken a range of actions this year in support of cryptoassets, the most prominent of which is the creation and passage of the GENIUS Act. Yet, it is far from clear that “payment stablecoins” (the focus of the GENIUS Act regulatory framework) will play a leading role outside of the crypto world in the future of payments. In this post, we highlight an important innovation of large banks – the creation of tokenized deposits -- that arguably will dominate stablecoins in traditional finance.

Acknowledgments. We thank Richard Berner, Yvan Dubravica, Jon Frost, John Lipsky, Richard Portes, David Wessel, and Lawrence J. White for helpful comments and discussions. We have submitted a version of this essay as a contribution to Dirk Niepelt, editor, Frontiers of Digital Assets, Currencies, and Payments, CEPR e-book, forthcoming.