Limiting Central Banking

“If central banks are the only game in town, I’m getting out of town.”

Then-Bank of England Governor Mervyn King, June 2013 (cited by Paul Tucker, May 14, 2018).

Since 2007, and especially over the past year, actions of public officials have blurred the lines between monetary and fiscal policy almost beyond recognition. Central banks have expanded both the scope and scale of their interventions in unprecedented fashion. This fiscalization risks central bank independence, thereby weakening policymakers’ ability to deliver on their mandates for price and financial stability. In our view, to find a way to back to the pre-2008 division of responsibilities, officials must establish clearer limits on what central banks can and cannot do.

Recalling the world before the 2007-09 financial crisis may seem quaint, but it provides a useful benchmark against which to measure how far the role of the central bank has evolved over the past dozen years. We start from the commonly agreed premise that, to meet its price stability (and employment) objectives, the central bank seeks to influence financial conditions. An easing or tightening of these conditions brings higher or lower growth and employment, which then influence inflation.

In a conventional pre-crisis framework, policymakers’ lever for control is the price of the central bank’s own liabilities. These commercial bank reserves are the safest, most liquid, and shortest maturity asset in the financial system, so their price is a benchmark for that of all other assets. By focusing on this one policy instrument, the central bank leaves financial markets to determine the price of maturity, liquidity, and credit risk.

Now, this conventional policy approach relies on well-functioning markets, so arbitrage can operate. For example, long-term nominal government interest rates reflect market perceptions of expected future short-term real interest rates, future inflation, and risks about the two. Pricing of private debt uses the equivalent-maturity government bond yield as a benchmark, adding a credit-risk premium that reflects investors’ views of default and recovery rates. Absent financial frictions, when monetary policymakers adjust the target interest rate on their reserve liabilities, the change ripples through the system influencing financial conditions, growth, and inflation.

Starting in 2007, the world changed dramatically. Frictions clogged the transmission mechanism from safe to risky assets, weakening the link between the central bank’s policy tool and financial conditions more broadly, reducing their ability to meet their objectives. Indeed, financial conditions turned sharply adverse despite conventional policy easing. After lowering the interest rate on their own liabilities to zero (or close), policymakers faced a new challenge. How could they further ease financial conditions when their conventional tool was no longer available?

Major central banks responded by intervening directly in a wider array of asset markets. They began large-scale purchases of both long-term sovereigns and quasi-public fixed-income securities. (Following the lead of emerging market central banks—like the Hong Kong Monetary Authority in August 1998—some jurisdictions went so far as to acquire equities.) And, where private intermediation became dysfunctional, policymakers substituted the central bank balance sheet for that of financial intermediaries and markets. In this way, policymakers remained able to influence financial conditions to stabilize prices and activity. Yet, in this initial shift to balance sheet policy, central banks mostly limited their acquisitions to the liabilities of governments and financial entities.

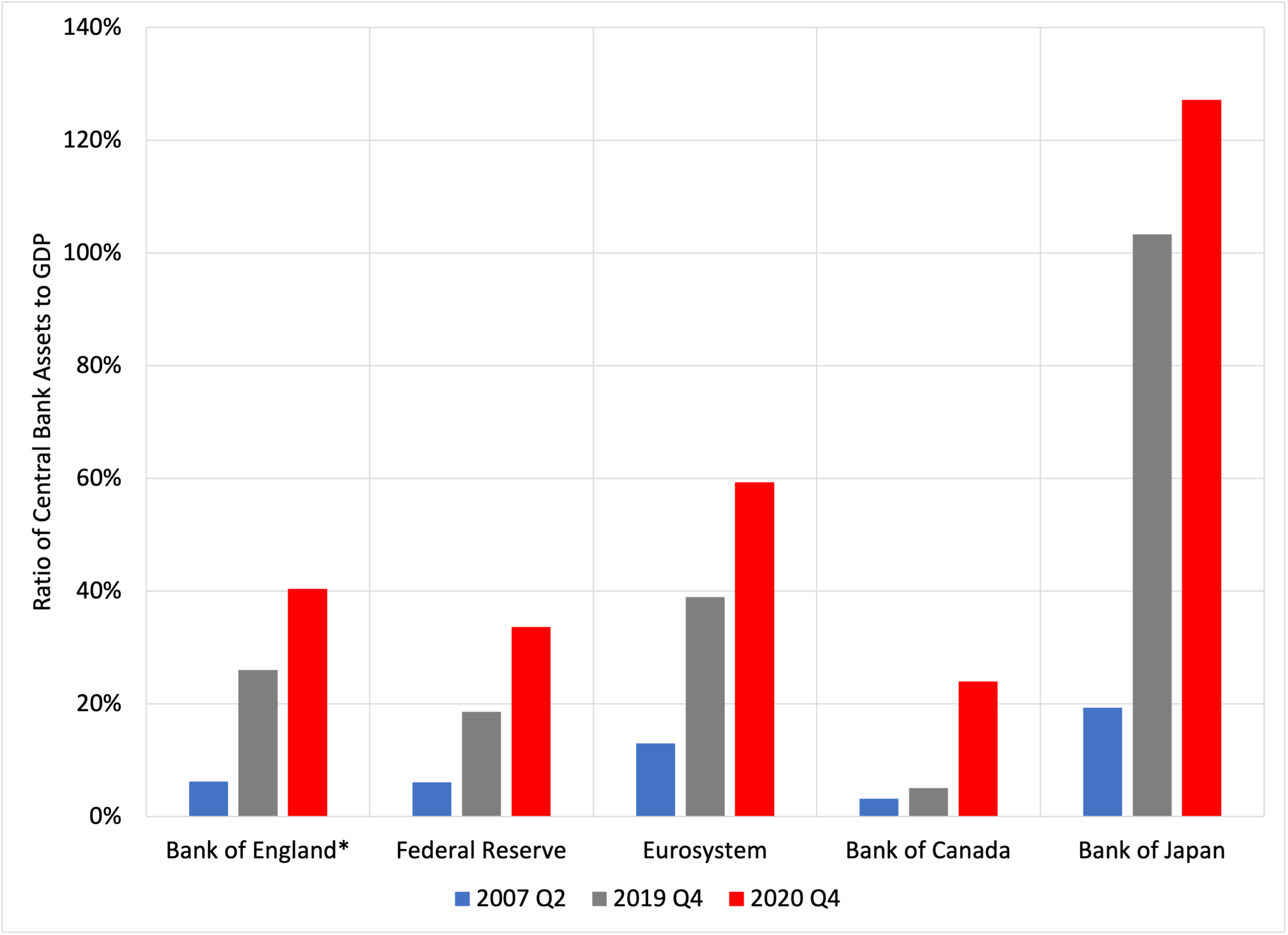

Reflecting this first stage of central bank expansion, the chart below shows the rise of central bank assets (as a percent of GDP) from 2007 to 2019. Comparing the blue and gray bars, note that the Fed’s assets rose by slightly more than 10 percent of GDP, the Bank of England’s by around 20, and the Eurosystem’s by over 25. The Bank of Japan is a clear outlier: in many ways Japanese central bankers were laying the path that others would tread when the pandemic hit.

Central bank assets as a percent of GDP: 2007, 2019 and 2020

Note: Observations for the Bank of England for 2019 and 2020 are likely understated as published data do not appear to be comprehensive (see here).

Source: Bank of England, Federal Reserve, Eurostat, Bank of Canada, Bank of Japan, and FRED.

These events are all recent enough that we can easily recall people’s stunned reactions. For example, we wrote on numerous occasions about how the Fed was managing its balance sheet (here), how they introduced new operating procedures (here), and how they might tackle the next downturn (here). But, like most people, we did not anticipate COVID or its enormous impact.

The pandemic introduced dangerous new obstacles to policy transmission. Even the market for U.S. Treasury securities, thought to be the deepest and most liquid in the world, showed signs of severe stress (see here). Widespread market disruptions compelled the Federal Reserve (and other major central banks) to go boldly where generally they had not gone before. In the United States, the Fed immediately re-activated nearly all the programs that it had created during the 2007-09 episode. Then, they went further—providing credit directly to the nonfinancial sector. This meant creating new vehicles for purchasing nonfinancial corporate debt and municipal debt. These lending programs aimed to increase credit supply quickly and directly through a broader substitution of the central bank’s balance sheet for that of private intermediaries. (See our contemporaneous descriptions here, here, and here.)

For the major central banks of the world, the impact of these pandemic response policies was even more dramatic than it was following the earlier crisis. Looking at the previous chart, note that central bank assets that accounted for less than 15% of GDP in 2007, are now between 25% in Canada and 60% of GDP in the euro area. Again, Japan is an outlier, with Bank of Japan assets exceeding 125% of Japanese GDP.

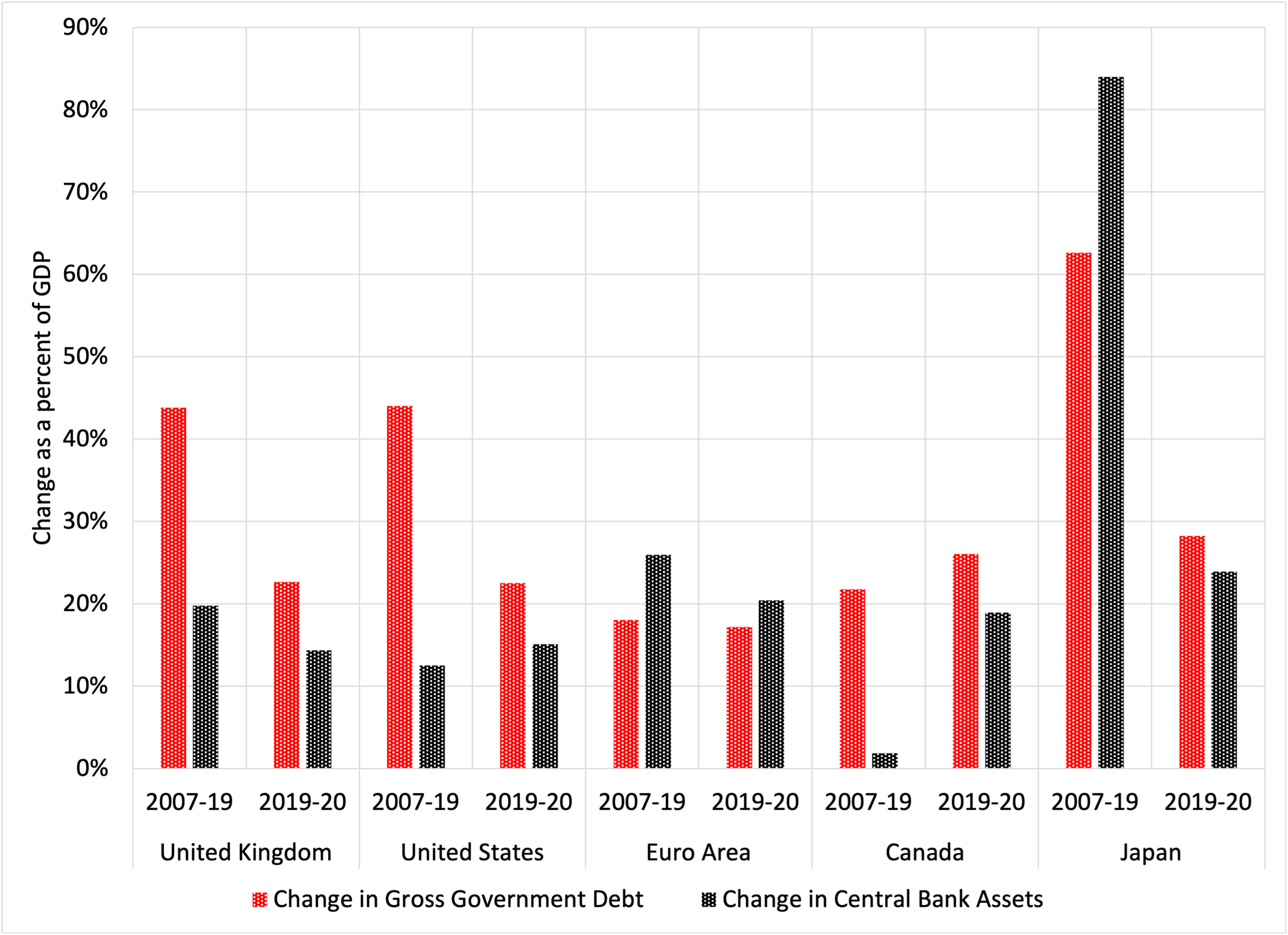

Not coincidentally, the extreme disruptions of the pandemic gave rise to unprecedented peacetime coordination among fiscal and monetary policymakers. The following chart highlights the resulting simultaneous (and ongoing) surge of gross government debt (in black) and central bank assets (in red). Prior to the pandemic, except in the euro area and Japan, the black bar is substantially lower than the red bar. Since 2019, however, central banks’ rapid asset expansions have absorbed between two-thirds and 120% of the increase in government debt.

Comparison of change in central bank assets and change in gross government debt (percent of GDP), 2007-2019 vs 2019-2020

Source: Various central banks, IMF World Economic Outlook Database, and FRED.

Where does this lead us? What will happen if central banks continue down this road, expanding their direct efforts to influence an ever-wider range of financial markets and asset prices? The answer is that, as the central bank’s balance sheet becomes larger and accounts for a growing share of intermediation, we will shift towards a world in which the state dominates credit allocation. (As we emphasize in an earlier post, the issuance of central bank digital currency creates exactly the same risks.) Should this happen, the dynamism of the economy and its ability to sustain even modest long-run growth would be vulnerable. Surely, that is not what central banks intend as a goal of their stabilization efforts.

In fairness to central bankers, they currently are under intense political pressure to expand their mandates. Not only that, but in a world of low interest rates and low inflation, fiscal policy has become the tool of choice for stabilization. Under these circumstances, it is extremely tempting (and very efficient) to use the central bank as the fiscal agent for government finance. This is what we call the fiscalization of the central bank.

Fiscalization is well short of fiscal dominance, where fiscal policymakers effectively control the volume of central bank money. Some observers, however, may find this distinction worryingly fine. In our view, the key danger from fiscalization is that when conditions become more tranquil, central banks will find it difficult to stop using the very politically sensitive tools that they introduced during the pandemic. Will the Federal Reserve immediately sell all liabilities of nonfinancial businesses and municipalities when it begins to taper its balance sheet expansion? Will the ECB return to limiting government debt acquisitions in line with euro-area members’ GDP? These challenges already loom large.

To be clear, it is important not to confuse the central bank balance sheet with the expertise of the central bank. Some people have claimed that, because central banks have technical and operational capacities, they should undertake a broader range of operations. We disagree. Central banks can provide technical assistance to the fiscal authorities, while keeping credit operations dictated by legislative authorities off the central bank’s balance sheet.

So, what should central banks do and not do?

First, it is fiscal authorities that ought to make the unavoidably political choices that directly influence resource allocation. Governments already have a myriad of institutions that do so. For example, the United States has government loan guarantee programs for housing, farm, small business, and student loans. Unelected central bankers should not control the scale and mix of programs like these. And governments should not conceal such fiscal actions on the balance sheet of the central bank. In a democracy, doing so lacks legitimacy and would become unsustainable.

As Paul Tucker notes in his excellent book, Unelected Power, legitimacy requires that appointed technocrats not engage in activities that primarily address the distribution of resources within a society (see here). Tucker also highlights the need to concentrate central bank authority where (as a result of the problem of time consistency) only they can achieve policy success at relatively low cost. This means restoring (as soon as possible) the focus on the traditional goals of price and financial stability.

At this stage, to ensure that central banks can do what they are designed to do well, we need to impose clear boundaries on the scope of what they are authorized to do, limiting both what they can buy outright and to whom they can lend. Doing this requires a fine balance, as we need to make sure that policymakers can still aid in a crisis. But, it should not be easy for policymakers to evade the restrictions. Most of all, we need a system in which central bankers are not left feeling that they are the only game in town, so that when monetary policy hits the limits of its effectiveness, they are not obliged to act in quasi-fiscal ways that threaten their legitimacy.

In this (and in other ways), to be successful, their discretion must be constrained.

Acknowledgements: One of us (Steve) presented an earlier version of these remarks at Nicolas Véron’s Peterson Institute Series entitled Financial Statements on 24 February 2021. You can find a video stream of the presentation (along with a discussion with Signe Krostrup of Danmarks Bank) here. We thank Nicolas and Signe for their probing comments and questions.